How We Secure Builds With fs-verity

We used to do our builds the "normal" way, but we have learned that it wasn't enough...

Secure software builds allow us to be confident that we are running and providing good and uncompromised software. Normal build security would check the software for known vulnerabilities, limit the number of dependencies, and call it a day. But we are a runtime security company, so that’s not enough.

With our builds:

If you unplug the network cable from our build VM, the build still finishes.

If someone modifies the Go compiler, the kernel refuses to execute it.

If a process outside the approved build chain attempts to read or write to protected build paths, a security eBPF program blocks the bad action at the kernel level.

We aren’t saying this is the only way to build software safely (it may be overkill). What we are saying is this is the level of control we wanted and needed.

Why We Went This Far

We have read Ken Thompson’s paper “Reflections on Trusting Trust” many times and understand the importance of the problem it describes.

We wanted to know how to verify that the exact toolchain used to produce a kernel-facing artifact was based on the source code that was committed. How do we verify that the toolchain was not modified between installation and use?

That led us to GCP VMs with custom images. We made sure not to use hosted runners since the most basic step in this journey was controlling the kernel, the boot chain, and all the tools used to create the artifact.

Why Not Github Actions

First of all, they are stuffed with bloatware, which is really nice when you don’t want to install dependencies manually, but really, really bad when you want any level of security. https://substack.bomfather.dev/p/githubs-ubuntu-latest-runners-have

Furthermore, we needed to pin and boot specific kernels (5.18 and 6.18), set boot flags such as lsm=bpf, enable fs-verity on the root filesystem, and manage the lifecycle of signing material during image construction.

All of this is awkward or impossible on generic hosted runners, where the kernel and boot chain are not under your control.

Because of this, we run on custom VMs built from Packer images, ensuring everything remains under our control.

What The Pipeline Actually Does

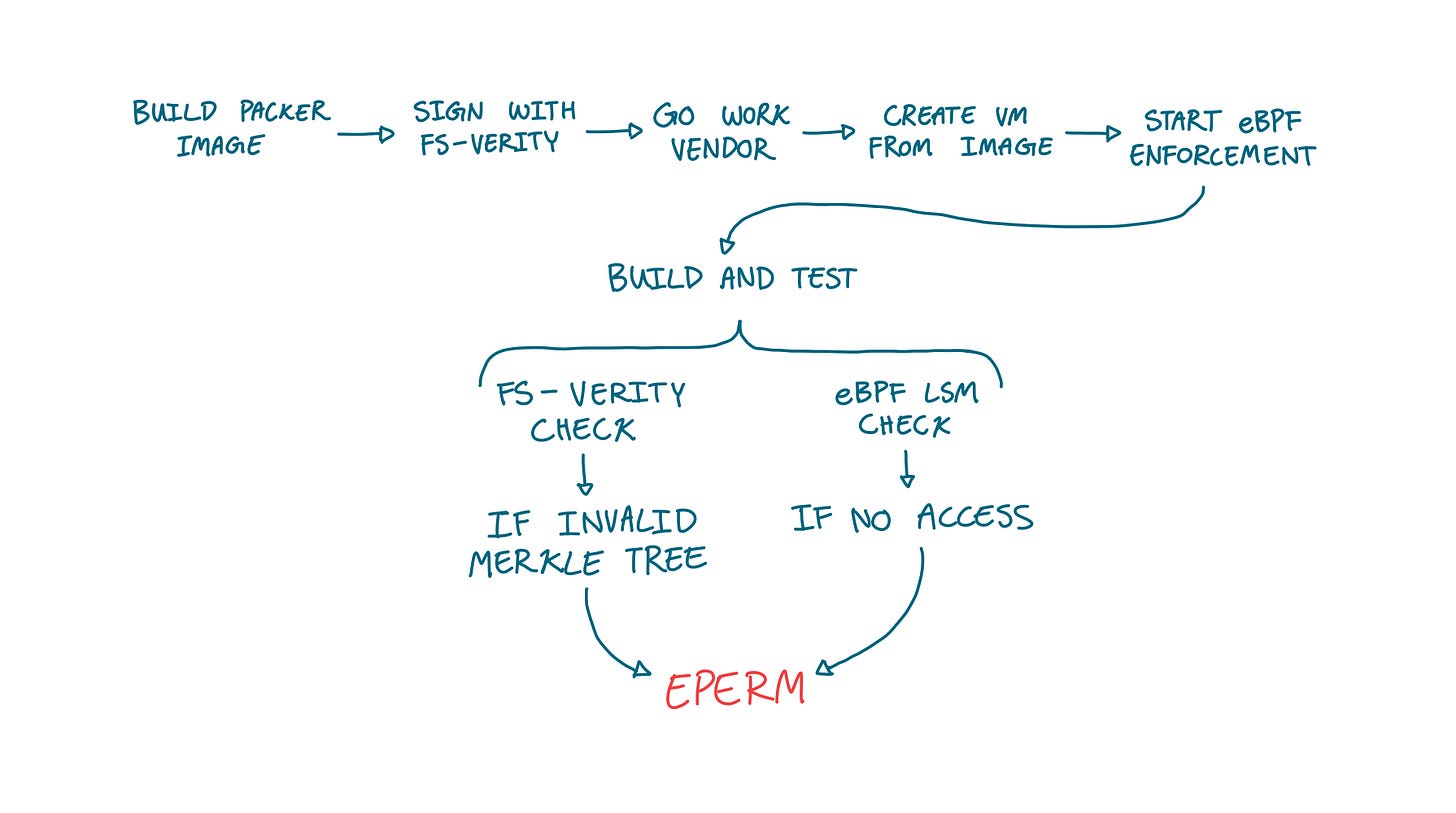

It has three stages, each with very different costs. First, we prebake a hardened image using packer with a pinned kernel and a signed toolchain with fs-verity enabled. Then we vendor dependencies with go work vendor. Finally, we build and test in a short-lived VM with GOPROXY=off (which tells go not to pull in dependencies or upgrades), and we are currently working on turning off internet access on the entire build machine.

Why We Use fs-verity Instead of Just Checksums

Checksums give us confidence that the binary is good at a certain point in time. With checksums, we can verify what we download. What it does not tell us is whether the binary we downloaded is the same as the one we execute at runtime.

fs-verity gives us that confidence, since it enforces that any binary that it monitors cannot be opened (and therefore executed) if the hash changes from boot. This is guaranteed by the Linux kernel and ensures that binaries are not modified after download and before execution.

This means that if a bad actor compromises your Golang executable, after your image is created, it can’t execute, and the whole build would fail.

What We Sign

We sign binaries that can influence build outputs, including the go toolchain internals, clang/LLVM, some supporting binutils, the protobuf toolchain, and other core build utilities.

This sounds really good, but in theory, it really isn’t. Whenever we want to upgrade anything, we need to do it manually. We need to rebuild our images, sign them, validate them, test that our builds pass, and ensure none of our security steps fail. While GitHub Actions may not be secure, it’s much easier to upgrade dependencies, utilities, and other components.

Dogfooding our eBPF Agent, by making it secure our Builds

This is the part we care about most, since running our security agent against our builds lets us constantly test and verify all our features in the real world.

We use the same eBPF LSM (Linux Security Modules) policy agent we ship to secure its own build. We have a couple of polices that allow us to significantly bump our security posture. The primary goal of our agents is to enforce expected behavior, so that bad binaries and processes cannot access resources they shouldn’t.

We first secure our own agent and make sure that nobody can tamper with its maps or where it stores its policies (https://substack.bomfather.dev/p/attacking-and-securing-ebpf-maps). We also make sure that nobody can shut down our agent, even if they have root privileges (https://substack.bomfather.dev/p/stopping-kill-signals-against-your-agent)

We restrict access to the source code directory so that only one binary is allowed to write to it, and another is allowed only to read from it. These are programs with simple, limited behaviors, so they can’t be compromised to do something bad. The best way to build a secure system is to use dumb, single-purpose components.

Our Next Steps to Integrate fs-verity with our eBPF Agent

fs-verity is a great tool that allows us to guarantee that the binaries we download are not tampered with, but we can do even more with it.

We are currently working on integrating fs-verity with our eBPF agent https://docs.ebpf.io/linux/kfuncs/bpf_get_fsverity_digest/. This would allow us to avoid relying on the filesystem for our policies and instead use hashes to verify them.

So if we had a policy that said “/app/server can access /app/db/databaseconnection.yaml”, now we could associate a hash with the server, allowing us to really confirm that our agent thinks that /app/server is the same /app/server we are talking about. Since Linux files can be mounted, moved, and hidden in bizarre ways, being able to associate a hash with them allows us to verify that we are granting access to legitimate processes.

Cost

Doing this is not fun or easy. Every single upgrade we have to do takes a really long time, and sometimes our upgrades break because a security policy triggers when we haven’t done every step right.

Frankly, if we were shipping a normal SaaS backend, this would be overkill.

But we aren’t. We are shipping kernel-level security software, and we’d rather spend extra build time than even risk a compromise.